India, a land of staggering diversity, holds countless surprises within its folds. Beyond the well-trodden tourist trails lie hidden corners where the atmosphere might, just for a moment, transport you to another country entirely. Imagine strolling down lanes reminiscent of provincial France, encountering architecture echoing Danish design, or finding villages with a tidiness often associated with Switzerland – all without needing a passport.

This journey explores seven such unique Indian villages: Mawlynnong, Tharangambadi, Cherrapunji and Nongriat, Puducherry, Malana, Majuli, and Khimsar. Each is said to possess an “international vibe,” a comparison often highlighted in travel narratives. While these comparisons offer a familiar starting point, the true enchantment lies deeper. These villages are not mere replicas; they are vibrant tapestries woven with unique histories, distinct local cultures, and resilient identities, profoundly Indian at their core. We delve beyond the surface similarities to uncover the authentic spirit and offbeat experiences these hidden gems offer, revealing a world of wonder contained entirely within India’s borders.

Table of Contents

7 Indian Villages with International Echoes: A Snapshot

| Village & State | International Comparison (Source Vibe) | Key Unique Indian Feature | Best Time to Visit (Brief) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mawlynnong, Meghalaya | Switzerland (Cleanliness) | Khasi Matrilineal Culture, Living Root Bridges, Community Ethos | October – April |

| Tharangambadi, Tamil Nadu | Danish/European Streets | Indo-Danish Colonial History, Fort Dansborg, Tamil Heritage | November – February |

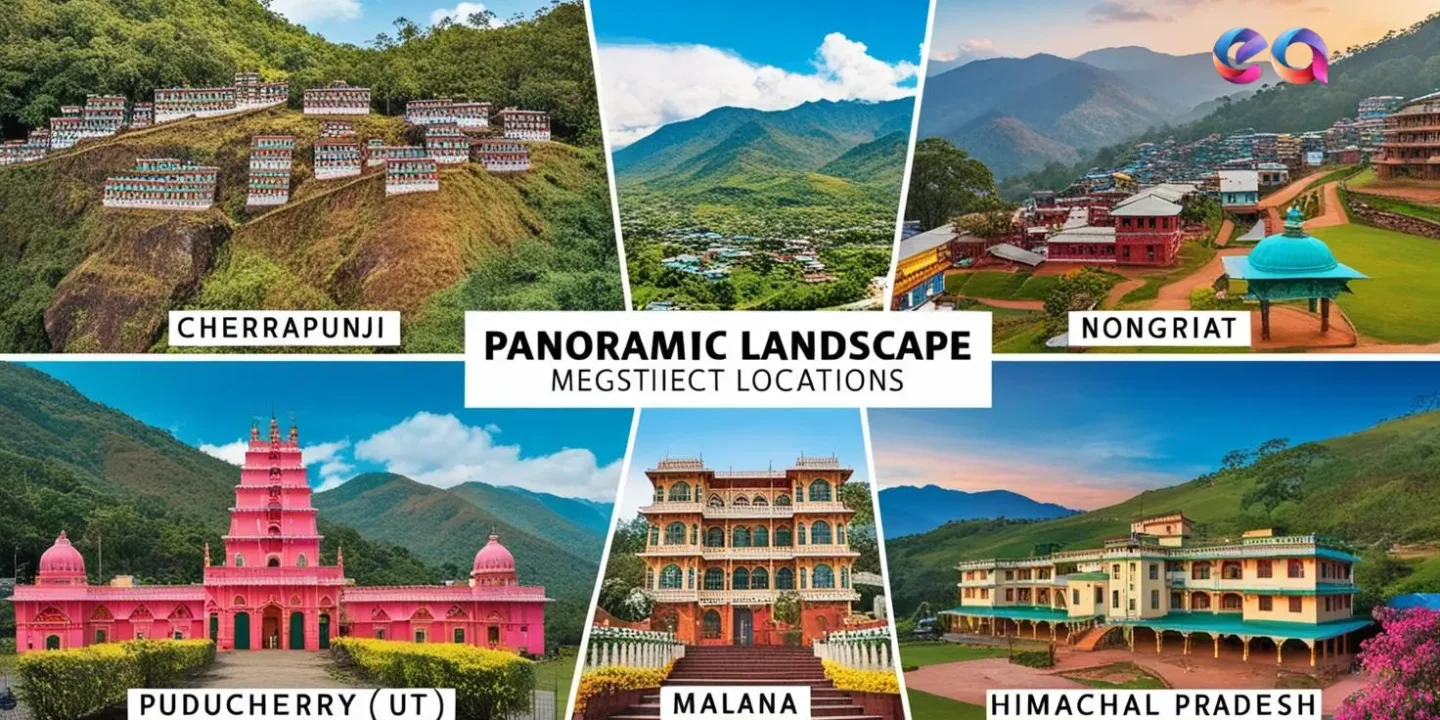

| Cherrapunji & Nongriat, Meghalaya | Costa Rica (Rainforest) | Extreme Rainfall, Khasi Bio-engineering (Living Root Bridges) | October – May (for trekking) |

| Puducherry (UT) | France | French Colonial Architecture, Franco-Tamil Culture, Auroville | October – March |

| Malana, Himachal Pradesh | Greek Democracy/Isolation | Ancient Theocratic Governance (Jamlu Devta), Kanashi Language | April – June, Sept – Nov |

| Majuli, Assam | Southeast Asia (River Island Culture) | World’s Largest River Island, Neo-Vaishnavite Satras, Erosion | October – March |

| Khimsar, Rajasthan | Arabian Nights (Desert) | Thar Desert Landscape, Rajput Heritage Fort, Marwari Culture | October – March |

Mawlynnong, Meghalaya: More Than Just Asia’s Cleanest Village (vs. Switzerland)

The comparison of Mawlynnong to Switzerland often surfaces, primarily linked to its remarkable cleanliness. This village in Meghalaya’s East Khasi Hills gained widespread recognition after being declared “Asia’s Cleanest Village” by Discover India magazine in 2003. However, this parallel, focusing almost solely on tidiness, barely scratches the surface. Mawlynnong’s essence isn’t found in alpine vistas but is deeply embedded in its unique Khasi cultural heritage, community-driven ethos, and harmonious relationship with its lush, subtropical environment.

The culture of cleanliness here is not a recent initiative for tourism but a deeply ingrained way of life, passed down through generations. Every resident, young and old, participates in maintaining the village’s pristine condition. Bamboo dustbins are ubiquitous, strategically placed throughout the village , and waste is meticulously segregated. Biodegradable waste becomes compost, nourishing the village’s gardens, while non-biodegradables are responsibly managed. Plastic bags are banned, and every household has functional sanitation. This collective responsibility stems from a profound respect for the land, a core tenet of the Khasi people who inhabit the village.

The Khasi community itself presents a fascinating social structure, distinct from much of India. They follow a matrilineal system, where lineage, name, and ancestral property pass down through the female line, typically to the youngest daughter (Ka Khadduh). This tradition inherently empowers women within the community and contributes to the strong social fabric and collective spirit evident in Mawlynnong. Their culture emphasizes a close connection with nature, reflected in sustainable farming practices and the reverence for sacred groves found elsewhere in the Khasi Hills. Mawlynnong also boasts a high literacy rate, indicative of the community’s value for education.

While the village itself is an attraction with its flower-lined paths and neat homes , several specific points of interest draw visitors. Perhaps the most iconic, though located in the nearby village of Riwai, is the Jingmaham Living Root Bridge. This single-level bridge is a stunning example of Khasi traditional ecological knowledge and bio-engineering, patiently ‘grown’ over years by guiding the aerial roots of the Ficus elastica tree across a stream. Its relative accessibility compared to the more remote double-decker bridge near Cherrapunji makes it a popular stop. Another feature is the Sky Walk or Brun Khongmen Viewpoint, a tall bamboo structure offering panoramic views over the village, surrounding hills, and sometimes even the plains of neighboring Bangladesh. The Balancing Rock, a large boulder resting naturally on a smaller stone, is a geological curiosity often imbued with local folklore. The century-old Church of the Epiphany (built 1902) adds another architectural dimension with its blend of European and local styles. Nearby Mawlynnong Waterfall provides a refreshing natural escape.

The village’s identity is intrinsically linked to its cleanliness ethic, a tradition rooted in Khasi culture and potentially reinforced by historical health events like past cholera outbreaks. This inherent characteristic gained external validation with the “Asia’s Cleanest Village” title, which significantly boosted tourism and local incomes. However, this influx of visitors brings challenges, such as littering by tourists. The community’s response—persisting with collective cleaning efforts, involving children, and maintaining their standards—demonstrates a conscious effort to preserve their core identity rather than letting it become merely a superficial attraction for tourists. Mawlynnong thus exemplifies a community navigating the delicate balance between leveraging its unique reputation for economic benefit and ensuring that cleanliness remains a deeply held cultural practice, reflecting a proactive model of community-based ecotourism.

Furthermore, the comparison to Switzerland, while perhaps intended as a compliment, proves misleading upon closer examination. It rests almost entirely on the abstract notion of cleanliness and orderliness. Geographically, Mawlynnong, with its subtropical flora, Khasi tribal culture, matrilineal society, unique living root bridges, and proximity to the Bangladesh plains, bears little resemblance to the alpine landscapes and distinct European cultural traditions of Switzerland. Such comparisons risk obscuring the village’s true, unique value, which lies in its specific Khasi heritage and its symbiotic relationship with the Meghalayan environment, not in mimicking a distant European nation.

Travel Practicalities for Mawlynnong:

Getting There: Mawlynnong is situated 90 km south of Shillong, the capital of Meghalaya, near the India-Bangladesh border. It’s accessible by road, typically via taxi or private car from Shillong, a journey of about 2-3 hours.

Best Time to Visit: While pleasant year-round , the post-monsoon and winter months (October to April) offer clear skies, lush greenery, and comfortable temperatures for exploring. The monsoon season (June to September) brings intense rain, enhancing the waterfalls and verdant landscape, but potentially causing travel disruptions.

Accommodation: The primary mode of accommodation is homestays run by local Khasi families, offering an authentic cultural experience and home-cooked meals. Options range from basic to more comfortable, with names like Mawlynnong Verde Cottage, Iapngar Homestay, and Khongwar Homestay mentioned in travel resources. Booking in advance, especially during peak season, is advisable.

Tharangambadi, Tamil Nadu: Echoes of Denmark on the Coromandel Coast (vs. Danish/European Streets)

On the Coromandel Coast of Tamil Nadu lies Tharangambadi, the “place of the singing waves”. More widely known by its Danish name, Tranquebar , this town holds the distinction of being the first Danish settlement in India. Established in 1620 through an agreement between the Danish East India Company, led by Admiral Ove Gjedde, and Raghunatha Nayak, the ruler of the Thanjavur Nayak Kingdom, Tranquebar served as a Danish trading post for over two centuries. Its unique atmosphere, characterized by European-style architecture and coastal setting, often leads to comparisons with Danish or European streetscapes. The Danish presence ended in 1845 when the settlement was sold to the British East India Company.

The lingering Danish vibe is most palpable in its architecture. Cobbled streets (though perhaps less prevalent now), colonial-era houses, European-style churches, and the imposing Fort Dansborg create a distinct atmosphere. The Town Gate, or Landporten, originally built in the 1660s and rebuilt in 1791, marks the entrance to the old town. King’s Street remains a central thoroughfare. Many buildings showcase a fascinating blend of Danish colonial and local Tamil architectural styles, reflecting the cultural exchange that occurred. Significant restoration efforts, often undertaken with Danish support from organizations like INTACH and the Danish Tranquebar Association, have helped preserve this unique heritage, especially after the devastating 2004 tsunami.

Central to Tharangambadi’s identity is Fort Dansborg, the second-largest Danish fort ever built, surpassed only by Kronborg in Denmark. Construction began in 1620, and the fort served as the administrative and residential heart of the colony. Its structure included ramparts, barracks, warehouses, kitchens, a jail, and residences for the governor and officials. A moat, now gone, once surrounded it. Today, the fort houses a museum displaying artifacts related to both the Danish period and the earlier Nayaka era, offering insights into the town’s layered history.

While the Danish colonial period left the most visible architectural imprint, Tharangambadi’s history is far more layered. Its existence as a trading port under the Pandya and later the Thanjavur Nayak kingdoms confirms its significance long before European powers arrived. Evidence suggests a pre-Danish presence of Portuguese missionaries and Indo-Portuguese communities as well. Following the Danes, the British took control, adding yet another colonial chapter. Therefore, viewing Tharangambadi solely through its “Danish vibe” overlooks this rich, multi-faceted past. It is fundamentally an ancient Tamil coastal town that experienced a defining Danish interlude within a broader history of local rule and successive colonial encounters.

The town’s narrative also presents a paradox of preservation and forgetting. After a period of neglect following India’s independence, significant restoration efforts, often driven by Danish interest and funding, have revived the key colonial landmarks. This focus on preserving the Danish heritage, while crucial for saving these structures, might inadvertently overshadow other aspects of the town’s history. The description of Tranquebar as a “forgotten” colony contrasts with its current status as a heritage tourism destination, particularly appealing to Danish visitors. This raises questions about which histories are being remembered and presented, and how the narrative is shaped by contemporary interests, including tourism and potentially, colonial nostalgia from various perspectives. The town’s revival is thus intertwined with a selective remembrance focused heavily on its visually distinct Danish past.

Travel Practicalities for Tharangambadi:

- Getting There: Tharangambadi is located on the Coromandel Coast in the Mayiladuthurai district of Tamil Nadu. It’s approximately 120 km south of Puducherry and 285 km from Chennai. The nearest major town is Karaikal (15 km south). The nearest railway stations are Nagapattinam (approx. 35 km) or Mayiladuthurai (approx. 31 km). Chennai International Airport (MAA) is the closest major airport. Road access via bus or taxi is common.

- Best Time to Visit: The winter months, from November to February or March, offer the most pleasant weather for exploring the town and its coastal setting.

- Accommodation: Heritage stays are a key attraction, notably The Bungalow on the Beach (Neemrana) and The Gate House (Neemrana). Several other hotels, resorts, and guesthouses are available in and around Tharangambadi and nearby towns like Karaikal and Thirukadaiyur

Cherrapunji & Nongriat, Meghalaya: Where Living Bridges Span Rainforest Realms (vs. Costa Rica)

The comparison of Cherrapunji and its surrounding areas, including the village of Nongriat, to the rainforests of Costa Rica likely stems from the region’s defining characteristics: exceptionally high rainfall, incredibly lush vegetation, and rich biodiversity. Cherrapunji, locally known as Sohra , sits in the East Khasi Hills of Meghalaya and holds historical fame as one of the wettest places on Earth. It boasts world records for the highest rainfall recorded in a single calendar month and year (in 1861). While the nearby village of Mawsynram currently claims the title for the highest average annual rainfall , Cherrapunji’s reputation endures. Its climate is classified as a mild subtropical highland (Köppen Cwb) , and the intense precipitation is primarily due to orographic lift – moisture-laden monsoonal winds from the Bay of Bengal being forced upward by the steep Khasi Hills. Interestingly, despite this legacy of rain, recent decades have seen shifts, with decreased overall volume and periods of water scarcity, possibly linked to climate change.

The most iconic and unique feature of this region, particularly associated with Nongriat village, is the network of living root bridges (Jingkieng Jri). These are not built in the conventional sense but are grown over decades by the indigenous Khasi and Jaintia peoples. By carefully guiding the pliable aerial roots of the Indian rubber tree (Ficus elastica) across rivers and gorges, often using temporary bamboo scaffolding, they create structures that intertwine, strengthen over time, and can last for centuries. The most famous example is the Umshiang Double-Decker Root Bridge in Nongriat, a unique two-tiered structure crossing the Umshiang River. These bridges are remarkably resilient, able to withstand the powerful monsoon floods, and hold immense cultural significance, representing a harmonious relationship between humans and nature. Their unique value has led to their inclusion on UNESCO’s tentative World Heritage list. Other notable bridges include the Ritymmen bridge near Nongthymmai village, reputedly the longest single root bridge , and the Mawsaw bridge further along the trail from the double-decker.

Beyond the bridges, the Cherrapunji area is a landscape sculpted by water, boasting numerous dramatic waterfalls, especially during the monsoon season. Nohkalikai Falls is India’s tallest plunge waterfall, a breathtaking sight as it drops 340 meters into a turquoise pool below. Nohsngithiang Falls, also known as the Seven Sisters Waterfall, features multiple parallel streams cascading down a limestone cliff, particularly spectacular during the rains. Other significant falls include Kynrem Falls (three-tiered, India’s 7th tallest), Dainthlen Falls (associated with Khasi folklore), and Rainbow Falls, a more secluded waterfall accessible via a further trek from Nongriat, known for the rainbows often visible in its spray on sunny days. The region is also known for its extensive cave systems. Mawsmai Cave is the most accessible and popular, offering a glimpse into the subterranean world of stalactites and stalagmites. Arwah Cave is another notable cave in the area. The overall landscape is one of dramatic cliffs, deep gorges, dense forests, and perpetually mist-shrouded valleys, creating a truly unique and atmospheric environment.

These living root bridges are more than just remarkable feats of natural engineering; they represent embodied cultural knowledge passed down through generations of Khasi people. The techniques, transmitted orally, demonstrate a deep understanding of the local ecosystem and a philosophy of patience, community collaboration, and working in harmony with nature. This approach, requiring decades for a bridge to mature, stands in stark contrast to modern infrastructure development and highlights a unique cultural worldview shaped by the specific challenges and opportunities of their environment.

While the “rainforest vibe” comparison to Costa Rica captures the general atmosphere of high rainfall and lush greenery , it simplifies the unique ecological and cultural context of the Cherrapunji-Nongriat region. This area is characterized by a specific subtropical highland forest ecosystem, shaped by extreme monsoonal patterns and the distinct geology of the Khasi Hills, including its limestone caves. Furthermore, the landscape is inextricably linked with the Khasi culture and its unique traditions, most visibly manifested in the living root bridges [multiple snippets]. This combination of specific geography, climate, and human cultural interaction creates a unique biome and cultural landscape that transcends generic rainforest analogies.

Travel Practicalities for Nongriat & Double Decker Root Bridge:

- Getting There: Access to Nongriat village and the Double Decker bridge is via a challenging trek. The trek starts from Tyrna village , reachable by road (taxi/bus) from Cherrapunji (Sohra), which is about 12-13 km away. Cherrapunji is approx. 54-60 km from Shillong.

- The Trek: The trek involves descending and ascending approximately 3,500 steep, often uneven, concrete steps. It crosses narrow, swaying suspension bridges made of steel wire. The round trip to the Double Decker bridge typically takes 4-5 hours , but allow significantly more time (8-10 hours round trip) if continuing to Rainbow Falls. The trek is considered moderate but strenuous due to the steps and humidity; good physical fitness is essential. Guides are available at Tyrna but not strictly necessary as the path is well-marked.

- Best Time to Visit: The post-monsoon and winter months (October to May) are generally preferred for trekking, offering drier paths and pleasant weather. Monsoon (June-September) showcases the waterfalls and greenery at their peak but makes the trek slippery, humid, and potentially hazardous.

- Accommodation: Options within Nongriat village are basic, consisting of a few homestays and guesthouses. Staying overnight allows for a more immersive experience and time to visit Rainbow Falls. Cherrapunji offers a wider range of accommodations, from luxury resorts like Polo Orchid Resort and Cherrapunjee Holiday Resort to budget guesthouses and homestays.

Puducherry: French Flair and Spiritual Sanctuaries (vs. France)

Puducherry, the Union Territory formerly known as Pondicherry , often evokes comparisons to France, earning nicknames like “Mini France” or the “French Riviera of the East”. This connection stems from its history as the former capital of French India. The French East India Company established a settlement here in 1674, and although control shifted periodically between the French, Dutch, and British, the French influence remained dominant until the territory’s de facto merger with India in 1954 (de jure in 1962/63).

The most tangible evidence of this legacy is the French Quarter, also known as Ville Blanche or White Town. This area retains a distinctly European character with its grid-patterned streets , often bearing French names like Rue Dumas, Rue Romain Rolland, and Rue Suffren. The architecture is characterized by colonial-style villas painted in soothing pastel yellows, pinks, and creams, adorned with arched doorways, louvered or shuttered windows, ornate wrought-iron balconies, and often hidden behind high compound walls. Bougainvillea cascades over walls and gateways, adding to the picturesque scene. This contrasts sharply with the traditional architecture of the Tamil Quarter (Ville Noire), located across the canal, which features elements like ‘thalvarams’ (pillared verandahs) and ‘thinnais’ (raised platforms for sitting).

Beyond architecture, a unique Franco-Tamil culture permeates Puducherry. The French language is still spoken by some residents, taught in certain schools, and visible on street signs. A number of inhabitants even hold dual French and Indian citizenship. The cuisine reflects this blend, with French bakeries offering croissants and pastries alongside restaurants serving classic South Indian fare and unique Franco-Tamil fusion dishes. Chic cafes, boutiques, and art galleries contribute to the town’s cosmopolitan atmosphere. Even festivals show this mix, with Bastille Day being celebrated alongside traditional Tamil festivals like Pongal.

Adding another layer to Puducherry’s identity is its significant spiritual dimension. The Sri Aurobindo Ashram, founded in 1926 by the philosopher-yogi Sri Aurobindo and his spiritual collaborator Mirra Alfassa (The Mother), is a major spiritual center located in the heart of the French Quarter. It attracts seekers worldwide interested in Integral Yoga and offers a tranquil space for meditation and contemplation, centered around the flower-laden Samadhi (final resting place) of Sri Aurobindo and The Mother. Just outside the town lies Auroville, the experimental international township established by The Mother in 1968. Conceived as a place for human unity beyond creed, politics, and nationality, Auroville is dedicated to sustainable living, spiritual research, and “unending education”. Its physical and spiritual focal point is the Matrimandir, a striking golden spherical structure designed for silent concentration. Visitors can learn about Auroville at its Visitors Centre and view the Matrimandir from a dedicated viewpoint.

Key attractions blend colonial heritage, spiritual sites, and coastal charm. The Promenade Beach (or Rock Beach) is a 1.5 km stretch perfect for walks, enjoying the sea breeze, and viewing landmarks like the impressive Mahatma Gandhi Statue, the French War Memorial, and the Old Lighthouse. Prominent churches include the Basilica of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, a stunning example of Gothic Revival architecture with beautiful stained-glass windows , and the Notre Dame des Anges Church, known for its Greco-Roman style and pink facade. Other notable buildings in the French Quarter include the historic Town Hall (Mairie/Hotel De Ville, currently under restoration) , the Romain Rolland Library (housing rare French volumes) , the French Institute , the Governor’s Palace , and heritage buildings now housing centers like the Cluny Embroidery Centre and the École Française d’Extrême-Orient library. For a different kind of historical exploration, the archaeological site of Arikamedu, an ancient Roman trading post, lies nearby. Paradise Beach, accessible by boat via the Chunnambar Backwaters, offers a more secluded sandy retreat.

The “French vibe” of Puducherry is undeniably present, but it’s important to recognize it as a carefully preserved and actively promoted aspect of the city’s identity, particularly within the distinct White Town. The clear demarcation between the French and Tamil quarters, a legacy of colonial planning, is maintained and often forms the basis of the tourist experience. While the Franco-Tamil cultural fusion is genuine , the visual narrative heavily emphasizes the French colonial architecture and associated lifestyle elements (cafes, boutiques). Restoration projects often focus on these colonial structures. This curation, driven partly by tourism and perhaps a degree of colonial nostalgia , shapes the “Mini France” perception. It highlights a specific, albeit significant, period of Puducherry’s history, potentially overshadowing its deeper Tamil roots and complex post-colonial reality.

Auroville, often included under the Puducherry umbrella, presents a different facet of “international.” Its global character arises not from historical colonization but from a conscious, philosophical effort to create a universal community. Founded by the French-born Mother based on the vision of Indian philosopher Sri Aurobindo , it draws residents from across the globe united by ideals of human unity, consciousness, and sustainable living. This aspirational, forward-looking internationalism contrasts sharply with the historical, architectural French colonial legacy of Puducherry town. Conflating the two under a single “French” or “international” label misses the distinct nature of each – one rooted in a specific colonial past, the other in a deliberate, future-oriented global experiment.

Travel Practicalities for Puducherry:

- Getting There: Puducherry is well-connected by road, located about 160 km south of Chennai. Chennai International Airport (MAA) offers the best air connectivity. Puducherry has its own smaller airport (PNY) with limited flights and a railway station (PDY). Auroville is approximately 10 km north of Puducherry town.

- Best Time to Visit: The cooler, drier months from October to March are generally considered the best time to visit, offering pleasant weather for exploring. Summers (March-June) are hot and humid, while the monsoon (June-September) brings heavy rain.

- Accommodation: Puducherry offers a wide spectrum of accommodation. The French Quarter boasts charming heritage hotels (like Hotel de L’Orient, La Villa, Palais de Mahé, The Promenade, Hotel Villa Victor) and boutique guesthouses. Auroville has numerous guesthouses reflecting its unique ethos, often requiring advance booking, especially during peak season (Dec-Mar). Standard hotels, budget guesthouses, and homestays are available throughout the town and surrounding areas.

Malana, Himachal Pradesh: Himalayan Isolation and Ancient Traditions (vs. Greek Democracy)

Deep within Himachal Pradesh’s Parvati Valley, shadowed by the towering peaks of Chanderkhani and Deo Tibba, lies Malana – an ancient village famed for its profound isolation and unique cultural practices. Its remoteness and distinctiveness have led to comparisons with ancient Greece, often centering on two intriguing, though debated, claims.

The first is the persistent legend that the Malanis are direct descendants of soldiers from Alexander the Great’s army who, weary after battles in India around 326 BCE, settled in this secluded valley. This theory is often bolstered by observations of the villagers’ distinct physical features and their unique language, Kanashi, which is unintelligible to outsiders. However, this captivating story lacks firm historical or genetic evidence. Linguistic studies categorize Kanashi not as a derivative of Greek, but as a Sino-Tibetan language, likely related to Kinnauri, spoken elsewhere in Himachal Pradesh. Furthermore, many Malanis themselves reportedly reject the Greek ancestry claim, identifying instead as descendants of their principal deity, Jamlu Devta. Ongoing genetic studies aim to shed more light on their origins.

The second comparison links Malana to ancient Greece through its system of governance, often romanticized as one of the “world’s oldest democracies”. The reality is a unique, indigenous system. Malana operates under a village council, the Hakima, which has two houses (upper and lower). However, ultimate authority rests with the village deity, Jamlu Devta (identified with the sage Jamdagni), whose decisions, often conveyed through an oracle, are considered final and binding. This theocratic structure, where the council acts as delegates of the deity, differs significantly from the principles of Athenian direct democracy, which involved broader citizen participation in assemblies. Scholars more accurately describe Malana’s system as a traditional theocratic oligarchy or republic, preserved through centuries of isolation.

Malana’s culture is defined by its isolation and the strict codes designed to maintain its purity and distinctiveness. The deity Jamlu Devta is central to their social fabric and governance. Their language, Kanashi, spoken only within the village and considered sacred, acts as a linguistic barrier, reinforcing their separation. Most striking to outsiders is the strict “touch-me-not” rule: visitors are forbidden from touching the villagers, their homes, temples, or any belongings. This practice stems from a belief in their own superiority (linked to the Aryan/Greek descent claims) and the need to protect their cultural and spiritual purity from outside contamination. Transgressions can result in fines, often used for ritual purification involving animal sacrifice. Visitors must adhere strictly to marked paths and respect these boundaries. Other rules reinforce their autonomy, such as prohibitions on police intervention within the village, restrictions on hunting, and strict endogamy (marriage outside the village leads to exile). Photography and videography may also be restricted.

The village is also widely known for “Malana Cream,” a potent form of hashish derived from cannabis plants cultivated in the valley. Historically, hemp and cannabis were integral to the local economy, used for making ropes, baskets, and as a legal cash crop. Since the 1980s, Malana Cream’s reputation has fueled recreational drug tourism, creating a complex situation where a traditional livelihood conflicts with Indian law and brings both income and notoriety to the village.

Attractions in Malana primarily revolve around its unique culture and stunning natural setting. The Jamlu Devta Temple, though inaccessible to outsiders, can be viewed from a distance. The village itself, with its traditional stone and wood houses clustered on the mountainside, offers a glimpse into a different way of life. The surrounding Parvati Valley provides breathtaking Himalayan scenery, including views towards Deo Tibba and the Chandrakhani Pass, making it a popular destination for trekkers.

The narrative comparing Malana’s governance to ancient Greek democracy is compelling but ultimately inaccurate when examined closely. Malana’s system, centered on the divine authority of Jamlu Devta and administered by a council, lacks the core tenets of citizen assembly and direct participation found in Athens. The “oldest democracy” label appears to be a romanticized interpretation, possibly originating from early observers or amplified for tourism, rather than an accurate political classification. What Malana truly represents is a remarkably preserved indigenous system of theocratic governance, sustained by religious faith and geographic isolation, which is fascinating in its own right, distinct from the Greek model.

Malana’s profound isolation has been instrumental in preserving its unique culture, language, and social structure against the tides of time. This seclusion, however, presents significant challenges. Limited economic opportunities have historically led to reliance on cannabis cultivation, placing the community in conflict with national laws. Access to modern education and healthcare facilities is restricted. Furthermore, generations of endogamy have resulted in reduced genetic diversity within the population. The increasing influx of tourism offers potential economic alternatives but simultaneously threatens the very cultural integrity that draws visitors. Malana thus exists in a delicate equilibrium, striving to maintain its ancient identity while navigating the complex pressures and opportunities of the contemporary world, with its isolation acting as both its shield and its vulnerability.

Travel Practicalities for Malana:

- Getting There: Malana is remote, located in the Parvati Valley, Kullu district. Access involves reaching the town of Jari (near Kasol) by road from Kullu or Bhuntar (nearest airport KUU). From Jari, a taxi can be taken to the Malana Dam/Nerang (entry gate), the closest motorable point. The final leg requires a trek of approximately 4-5 km (1.5-2 hours). Longer, multi-day treks via Rasol Pass or Chandrakhani Pass also exist.

- Trek Difficulty: The main trek from the entry gate is considered moderate, involving steep ascents and descents on a defined, sometimes rocky path. Reasonable physical fitness is required.

- Best Time to Visit: The summer months (April to June) and post-monsoon autumn (September to October/November) offer the most favorable weather for trekking and visiting. Winters (December to February) bring heavy snowfall, often making the trek inaccessible or dangerous. The monsoon season (July-August) should be avoided due to heavy rains, slippery trails, and potential landslides.

- Accommodation: Due to the village’s strict rules, accommodation options for tourists are limited and located outside the main village boundaries. These typically consist of basic guesthouses, homestays, or campsites. Advance inquiry is recommended. Many visitors opt to stay in nearby Kasol or Jari and make a day trip/trek to Malana.

Majuli, Assam: Life on the World’s Largest River Island (vs. Southeast Asia)

Majuli, nestled within the vast expanse of the Brahmaputra River in Assam, holds the title of the world’s largest river island – although this status is under constant threat. Its unique riverine setting, vibrant tribal cultures, and distinct artistic traditions sometimes draw comparisons to Southeast Asia. Formed over centuries by the shifting dynamics of the Brahmaputra and its tributaries like the Subansiri , Majuli presents a landscape of lush paddy fields, numerous wetlands (beels), and scattered villages.

A critical aspect of Majuli’s existence is the relentless erosion caused by the powerful Brahmaputra River. The island’s landmass has shrunk dramatically over the last century, from over 1200 sq km historically to less than 500 sq km in recent estimates. This ongoing erosion displaces communities, impacts livelihoods like farming and pottery (due to loss of land and access to traditional clay sources), and poses a significant threat to the island’s future.

Culturally, Majuli is revered as the cradle of Assamese civilization and the heartland of Neo-Vaishnavism, a reformist Hindu movement initiated by the 15th-16th century saint-reformer Srimanta Sankardeva and his disciple Madhavdeva. Sankardeva established the institution of the Satra – monasteries that serve as centers for religious practice, cultural preservation, artistic expression, and education. Originally numbering over 60, around 22 Satras remain active today due to erosion. Prominent Satras include:

- Kamalabari Satra: Known for arts, literature, classical studies, and traditional boat building. Its Uttar Kamalabari branch has propagated Sattriya art internationally.

- Auniati Satra: Famous for religious observances like Paalnaam, Apsara dances, and housing a rich collection of ancient Assamese artifacts.

- Dakhinpat Satra: A major center, particularly known for its elaborate Raas Leela performances during the Raas Mahotsav.

- Garamur Satra: Also known for Raasleela and for preserving historical weapons like cannons (Bortop).

- Samaguri Satra: Globally renowned for its unique tradition of mask-making (Mukha Shilpa), essential for Bhaona performances.

The island is also home to diverse indigenous tribal communities, primarily the Mishing (the largest group), Deori, and Sonowal Kachari. These communities, many belonging to Tibeto-Burman linguistic groups with origins traced possibly to Arunachal Pradesh or further north , have adapted their lifestyles to the riverine environment. They typically live in villages near the river, often in traditional stilt houses (Chang Ghars) made from bamboo to cope with floods. Their livelihoods revolve around agriculture (paddy, mustard, pulses) , fishing , and traditional crafts. Festivals like the Mishing spring festival Ali-Ai-Ligang and the Deori agricultural festival Bisu mark their cultural calendars.

Majuli is a vibrant center for traditional Assamese arts and crafts, nurtured both within the Satras and the tribal communities. The mask-making (Mukha Shilpa) at Samaguri Satra is particularly famous, creating expressive masks from bamboo, clay, and cloth for use in Bhaona, the traditional religious dramas introduced by Sankardeva. Weaving is another prominent craft, especially among Mishing women, who create intricate textiles like Gamosas and Mekhla Chadors on traditional handlooms, often set up beneath their stilt houses. Traditional pottery, uniquely made without a potter’s wheel, is another heritage craft, though threatened by erosion impacting clay sources. Boat building is associated with the Kamalabari Satra. The Satras are also repositories of Sattriya Nritya, a classical dance form originating from Sankardeva’s teachings, and Borgeet, devotional songs.

The island’s extensive network of wetlands (Beels) makes it a significant biodiversity hotspot, particularly for birds. Majuli attracts numerous resident and migratory bird species, including endangered storks and vultures, making it an Important Bird Area (IBA) and a paradise for birdwatchers, especially during winter. The wetlands are crucial habitats, but their area and health are declining due to factors like erosion, the construction of embankments disrupting natural flood cycles, and agricultural expansion. Despite its ecological significance, Majuli has not yet been designated a Ramsar site, a status that could aid conservation efforts.

Majuli’s existence is a testament to cultural resilience in the face of extreme environmental fragility. The constant threat of erosion from the Brahmaputra shapes life on the island. Yet, amidst this vulnerability, Majuli sustains a vibrant cultural landscape, anchored by the Neo-Vaishnavite Satras and the distinct traditions of its tribal communities [multiple snippets]. The Satras preserve not only religious practices but also classical Assamese arts, while tribal lifestyles demonstrate adaptation to the riverine environment. This suggests that the island’s endurance relies heavily on its cultural fabric, embodying adaptation and continuity. Majuli’s unique value lies in this dynamic interplay between a powerful, ever-changing river system and a deeply rooted, resilient human culture, a living cultural landscape nominated for UNESCO World Heritage status.

The comparison to Southeast Asia , while perhaps suggested by visual elements like stilt houses or the riverine focus , remains vague and potentially superficial. Southeast Asia encompasses immense diversity. While some anthropological links might exist (e.g., Tibeto-Burman origins of some tribes ), Majuli’s dominant cultural identity is profoundly shaped by the unique Assamese Neo-Vaishnavite tradition and the Satra institution, which are specific to this region of India [multiple snippets]. Focusing on this distinct Satriya heritage offers a more accurate and richer understanding than a broad, generalized comparison to Southeast Asia.

Travel Practicalities for Majuli:

- Getting There: Majuli is an island and primarily accessed by ferry. The main ferry point is Nimati Ghat, located near Jorhat town in Assam. Ferries run regularly (usually 6 days a week, check schedules) to Kamalabari Ghat or other points on Majuli. A Ro-Ro (Roll-on/Roll-off) ferry service is also available, capable of transporting vehicles. Jorhat is the nearest major town with an airport (JRH – Rowriah Airport) and a railway station, connecting it to Guwahati and other parts of India. From Jorhat town/airport/station, one needs to travel by road (taxi/bus) to Nimati Ghat (approx. 14 km) to catch the ferry.

- Best Time to Visit: The winter months, from October/November to March/April, are considered the best time to visit Majuli. The weather is pleasant, dry, and ideal for exploring the island and birdwatching. The Raas Mahotsav, a major cultural festival celebrating Lord Krishna, takes place in mid-November and is a popular time to visit. The monsoon season (June-September) should generally be avoided due to heavy rains, flooding, and potential disruption of ferry services.

- Accommodation: Majuli offers unique accommodation experiences, primarily in the form of bamboo cottages, guesthouses, and homestays run by local families or communities. Some Satras may also offer basic accommodation for visitors/devotees. Popular options mentioned include La Maison de Ananda, Ygdrasill Bamboo Cottage, Okegiga Homes, and various Satra guesthouses. Booking in advance is advisable, especially during peak season or festivals.

Khimsar, Rajasthan: Regal Forts and Desert Mystique (vs. Arabian Nights)

The comparison of Khimsar to the tales of the Arabian Nights likely arises from its dramatic setting on the edge of the vast Thar Desert in Rajasthan. Images of golden sand dunes stretching towards the horizon, camel caravans, and a magnificent, history-laden fort easily evoke the exoticism and romance associated with those ancient stories. Khimsar is a small village located in the Nagaur district of central Rajasthan, situated roughly halfway between the cities of Jodhpur and Bikaner.

The centerpiece of Khimsar is its formidable fort, a structure steeped in history and royal legacy. Built in 1523 AD by Rao Karamsji, the 8th son of Rao Jodha (the founder of Jodhpur), the fort occupies a strategic position on the desert’s edge. Its battle-scarred walls and turrets bear witness to centuries of history, including serving as a temporary residence for the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb. Over time, additions were made, including a zenana (ladies’ wing) in the 18th century and a new royal wing in the 1940s by Thakur Onkar Singh. The architecture reflects a blend of robust Rajput military design and later influences. Today, a significant portion of the Khimsar Fort has been meticulously converted into a premier heritage hotel, managed by the Welcomhotel by ITC Hotels group. Spread over 11 acres, it offers luxurious rooms and suites within the historic structure, alongside modern amenities like swimming pools, a spa (Vishranti/Kaya Kalp), restaurants (Fateh Mahal, Vansh), bars, and recreational facilities, while preserving the original grandeur. A part of the fort remains the residence of the royal descendants. The hotel has received the prestigious “Grand Heritage Award for Excellence” from India’s Department of Tourism.

Complementing the fort experience is the Khimsar Dunes Village, a unique retreat situated about 6-8 km from the main fort, deeper into the sand dunes. Accessible only by jeep or camel , this eco-friendly setup offers accommodation in traditional Rajasthani style mud huts or luxury tents nestled around a small oasis. It provides an immersive desert experience, complete with camel rides, jeep safaris, stunning sunsets over the dunes, bonfires, and traditional Rajasthani folk music and dance performances under the stars. Note that the Dunes Village typically operates seasonally, closing during the hottest summer months (usually open October to March).

Beyond the fort and dunes, Khimsar offers a window into the local Marwari culture of Rajasthan. Visitors can explore the village, interact with locals, and observe traditional life. Rajasthani traditions are rich in folk music and dance (like the Kalbelia dance often performed for guests) , vibrant textiles and handicrafts found in local markets , and distinct cuisine, with dishes like Dal Baati Churma being staples. The nearby town of Nagaur hosts the famous Nagaur Fair, primarily a large cattle trading event but also featuring cultural activities like camel races and tug-of-war, offering a vibrant spectacle usually held in January or February.

Adventure and exploration activities are central to the Khimsar experience. Camel safaris allow leisurely exploration of the desert landscape and nearby villages. Jeep safaris offer a more exhilarating way to traverse the dunes and reach points of interest. Wildlife enthusiasts can visit the nearby Panchala Black Buck Reserve, a sanctuary protecting significant populations of blackbuck, chinkara (Indian gazelle), and nilgai (blue bull) antelopes. The Dhawa Doli Wildlife Sanctuary is another nearby option. Other activities can include exploring local temples, visiting the historic Nagaur Fort , or simply enjoying the tranquility and dramatic sunsets of the Thar Desert.

While the “Arabian Nights” comparison captures the romantic allure of the desert setting – the dunes, camels, starry nights, and the imposing fort – it’s essential to ground the experience in its specific Rajasthani context. Khimsar’s history is deeply tied to the Rajput clans of Marwar, their codes of chivalry, and their unique architectural styles, which blend military pragmatism with intricate artistry. The local culture is distinctly Marwari/Rajasthani, with its own specific traditions, music, dance forms (like Ghoomar, Kalbelia), cuisine, and festivals (like Nagaur Fair). The comparison to the broader, perhaps more Middle Eastern-centric imagery of “Arabian Nights,” while evocative, should not overshadow the rich, specific heritage of Rajasthan that defines Khimsar.

The transformation of Khimsar Fort into a heritage hotel, alongside the development of the Dunes Village, represents a significant shift towards tourism as a key economic driver for the area. This model successfully preserves the magnificent fort structure while providing employment and showcasing local culture to visitors. However, as with any heritage tourism project, it involves a careful balancing act – maintaining authenticity while providing modern luxury, managing visitor impact on the fragile desert environment, and ensuring that the economic benefits reach the wider local community beyond the immediate hospitality operations. The success of Khimsar lies in its ability to offer a luxurious yet culturally grounded experience, leveraging its history and landscape for sustainable tourism.

Travel Practicalities for Khimsar:

- Getting There: Khimsar is located in Rajasthan’s Nagaur district, on the Jodhpur-Nagaur-Bikaner highway. The nearest major city, airport (JDH), and railway station is Jodhpur, approximately 90-95 km away (about a 2-hour drive). Nagaur also has a railway station (approx. 43-50 km away) but Jodhpur offers better connectivity. Khimsar is accessible by road via taxi or bus from Jodhpur, Jaipur, Bikaner, and other Rajasthani cities.

- Best Time to Visit: The winter months, from October/November to February/March, are the best time to visit Khimsar. The weather during this period is pleasant for desert activities and sightseeing. Summers (April-June) are extremely hot, and the monsoon season (July-September) sees some rainfall but can still be hot and humid. Visiting during the Nagaur Festival (usually Jan/Feb) offers a vibrant cultural experience.

- Accommodation: The primary accommodation options are the Welcomhotel Khimsar Fort & Dunes (heritage hotel within the fort) and the associated Khimsar Dunes Village (luxury huts/tents in the dunes). Booking in advance is essential, especially during peak season.

Conclusion: A World Within India

The exploration of these seven distinct villages – Mawlynnong, Tharangambadi, Cherrapunji/Nongriat, Puducherry, Malana, Majuli, and Khimsar – reveals a fascinating aspect of India’s immense diversity. While initial comparisons to international locations like Switzerland, Denmark, Costa Rica, France, Ancient Greece, Southeast Asia, or the settings of Arabian Nights offer an intriguing entry point , they ultimately serve only as faint echoes. The true resonance of these places lies not in their resemblance to elsewhere, but in their unique embodiment of India’s varied landscapes, complex histories, and deeply rooted local cultures.

From the community-driven cleanliness and matrilineal traditions of the Khasi in Mawlynnong to the layered colonial history and enduring Tamil heritage beside the Danish fort of Tharangambadi ; from the breathtaking natural engineering of living root bridges in the rain-soaked Khasi hills around Cherrapunji and Nongriat to the palpable French colonial legacy blending with Tamil life and Auroville’s unique spiritual internationalism in Puducherry ; from the ancient, isolated traditions and unique governance system under Jamlu Devta in Malana to the vibrant Neo-Vaishnavite culture of the Satras and tribal life persisting against the odds on the eroding river island of Majuli ; and the regal Rajput history embodied in Khimsar Fort against the stark beauty of the Thar desert – each location tells a profoundly Indian story.

These villages demonstrate that seeking global experiences does not always require crossing international borders. They offer journeys into distinct cultural pockets, showcasing unique architectural styles, social structures, artistic traditions, and ways of life that have evolved within the Indian subcontinent. They remind us that India is not a monolith but a mosaic, containing worlds within worlds. Exploring these “hidden gems” provides not just a picturesque escape but an opportunity to appreciate the depth and resilience of local heritage, often preserved through isolation, community effort, or a unique blend of historical influences. They stand as testaments to the fact that sometimes, the most exotic and transporting journeys are those taken within one’s own country, discovering the diverse and fascinating realities that make India truly incredible.